|

|

|

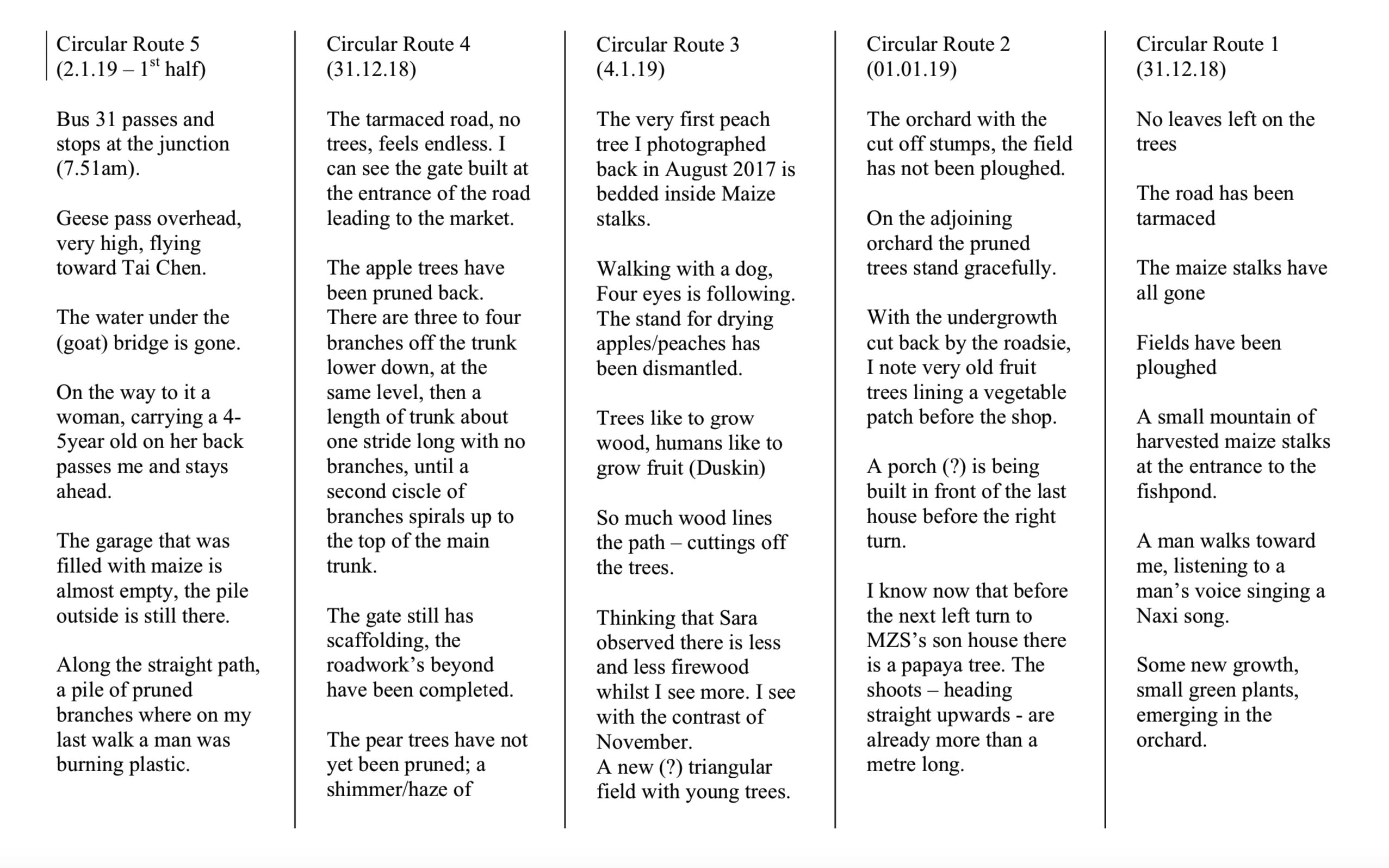

Er Ge later paved the courtyard of Lijiang Studio with founded stones and planted several trees there. (photo taken in 2007) |

In 2004, Zhengjie, the founder of Lijiang Studio rented a traditional folk house in Jixiang Village, Lashi Town, Yulong Naxi Autonomous County in Lijiang City of Yunnan Province, and transformed it into a living space as well as an artist’s studio for resident artists. Next-door to the studio live the owner of the house, Er Ge (literarily translated as “the second brother”; a designation often given to the second son of a family), and his family. As the coordinators of the studio, they not only provide resident artists with meals and other daily support but also help the artists acquire local knowledge, communicate with the folks, and develop art projects.

|

|

|

Er Ge later paved the courtyard of Lijiang Studio with founded stones and planted several trees there. (photo taken in 2007) |

Lijiang City, located in the northwestern part of Yunnan, sits on the major thoroughfares that link Yunnan, Sichuan, and Tibet. Covers a total area of 20,600 square kilometers, the area is divided into four counties and one district. Up to the end of 2017, Lijiang had a population of 1.29 million, of which half were non-Han Chinese. Though the city is located in a low-altitude region, it has a high elevation above the sea level, stretching across a terrain high in the north and low in the south. Caught between the Hengduan Mountains and the Himalayas from east to west, it is in a region through which three major rivers (the Jinsha River, the Nu River, and the Lancang River) run in parallel. Varying in landform and demonstrating climate features of subtropical, temperate, and frigid zones, the region is thus extremely rich in biodiversity. Jixiang Village, where Lijiang Studio is located, is in La City western to the Old Town of Lijiang and southern to Lashi Lake National Wetlands Park. The village, administratively belonging to Yulong Naxi Autonomous County, is a traditional ethnic settlement of Naxi people. The Naxi culture is characterized by pluralism and inclusiveness. Especially, its most prominent branch, namely the Dongba culture, has a long history that has been handed down to this day. The Dongba culture uses a unique hieroglyphic scripture and extensive ritual systems as its carriers. It has assimilated and integrated elements from the Indian, Tibetan, and Han Buddhist cultures to construct its peculiar belief system that bears the traits of both natural and revealed religions. Today, only a few inheritors of the Dongba culture still stay familiar with their classics, master the Dongba hieroglyphs, and know how to perform the Dongba rituals.

For Jixiang Village is adjacent to the famous Lashi Lake Wetlands Park and overlooks the Yulong Mountain, most local people there hope to advance regional development through promoting cultural and ecological tourism as well as agricultural products. Meanwhile, this social condition has also shaped the cultural identity of the place. On the one-hour-and-half bus trip from Jixiang Village to downtown Lijiang, the view one may encounter the most – apart from the splendid countryside sceneries – are tourists on horsebacks and giant billboards with commercial of major local goods. It is precise in this rural environment undergoing rapid transformations that Lijiang Studio is situated.

In 2005, China launched the policy of “building a new socialist countryside,” which implemented industrial reformations and the confirmation, registration, and licensing of land ownership in rural areas. Before that, Er Ge’s family maintained self-sustaining by mainly growing corn, rice paddies, wheat, lentils, and peas, among others. Since then, their family land has been taken over by the government, leaving them only seven out of the original twenty acres of land. Now, the family has also begun to grow economic products such as apples and pears, while having to buy food supplies from the market. The seeds Er Ge and his family use to grow these products are also commercial seeds, just as in other local farmers’ homes.

|

|

Lashi Lake (October 2018) |

|

|

|

Jixiang Village (March 2019) |

|

|

|

Lashi Lake (March 2019) |

Over more than a decade, Lijiang Studio has held over one hundred residencies and many artists’ works are preserved in the studio or placed at other locations in the village such as public spaces, residents’ homes, and various art spaces. The staff of the studio concerns mostly about how the artists can give full play to their creative capacities. When applying for the residency, the artist does not have to propose a specific theme for work but only needs to explain why he or she wishes to do a residency here. Meanwhile, the time for the residency is also negotiable according to the artist’s needs. In general, the artists who make their applications to the studio would naturally hold a deep interest in the local life of the region. The fact that the studio adopts a co-living model accordingly allows the artists to merge artistic practice, everyday life, and research. Meanwhile, the residency experience would also be influenced by the rhythm of local life and economic production, including the revisit and practice of concepts such as “sharing” and “generosity” that pertain to interpersonally relationships.

|

|

Looking out from the windows on the second floor of Lijiang Studio, one can see the top of Yulong Mountain, where the scenery transforms with the change of seasons and lights. The studio once named its work during a certain period “the place that sees the glacier,” which denoted its mission to explore the individuals’ perception of the surrounding, the studio’s relationship with the local natural environment, and the experience of collective learning. |

Here, three projects of Lijiang Studio are introduced: “A-lla-la-lei,” “Distortion of Distortion Recipes,” and “Qilin Dance.” The three projects touch upon various issues and encompass a wide range of practical methods. They demonstrate the directions to which the participating artists’ longitudinal practices lead and have been continuously evolving in-depth as the new participators join in. Though the three projects started from an ecological ground, they do not target at framing themselves within the domain of ecological practices and correspondingly giving a comprehensive definition to the field but attempt to explore this following issue: how nature – as an outcome of local social organizing rather than an empirically experienced existence – interacts with the works of artists; how Lijiang Studio, as a solid entity that has accompanied and co-developed with Jixiang Village, responds to and participate in the formation of the communal ecology of the village? As these projects only intend to delineate certain aspects of these practices, they are less comprehensive summarizations of the above discussions than invitations that encourage the viewers to explore and open up new routes leading to an ecologically informed reading into these practices.

|

|

In the village and within the studio, activities such as casual chat and dining often take place in “shàzi,” an open space in front of the corridor of the house. The kitchen in Er Ge’s house is also built in an open space facing the courtyard. Many major discussions regarding the studio’s projects took place here. (photo taken in February 2019) |

|

|

A corner of Lijiang Studio where the shàzi of the house faces the courtyard. (March 2019) |

If the reader wants to explore more about Lijiang Studio, they may start with a tour on the website of the studio and the personal pages of individual artists. For example, artist Sarah Lewison documented the transformation of local agricultural practice from the traditional, self-sufficient model to large-scale farming and how policies on tourism and agricultural businesses influence the life of local peasants (Naxilandia in the 17th, three/four-channel video installation, size variable, 70 minutes, 2017); artist Duskin Drum explored with local villagers’ strategies of mushroom growing and environmental conservation in his project “World Heritage Beer Garden Picnic” (2018); meanwhile, the musicians also enjoy carrying out improvisations and making filed recordings here. The artists’ explorations were not acts out of nostalgia: as their practices evolved with the hesitations and the will to stay manifested by different parties involved in the “development” of the village and coped with the pressures laid by realities on their cognitive and perceptive spaces, humor, whimsy, idleness, actions that can be regarded as “artwork,” and some shared time and perceptions had gradually appeared to them. Compared with ideas of the static, idyllic “natural” landscapes and the “multicultural” feast that the tourism business tends to promote, the artists’ mobile perspectives offer alternative interpretative methods for approaching Lijiang. At the same time, these artistic practices are also generating a new terrain on which solid networks are built to connect the activists in the region, thus providing possibilities for transforming the local consciousness and reforming the rationale of actions. As the artists continuously revisit the place, this process is also propelled to develop into depth. It has come to the practitioners’ realization that apart from simply protecting the village as a historical heritage or ignoring its regional idiosyncrasies in the name of development, there are still other possibilities.

|

|

|

“A-lla-la-lei” |

On a sunny afternoon in late March 2019, a group of people gathered by the family vegetable plot behind the kitchen of Lijiang Studio, standing around a strange installation. From a distance, it looked a bit like a haystack commonly spotted in the village, but the color was more complicated. If you come closer, you would find that the “haystack” is weaved out of bamboo strips -with an opening left on one side of the installation – and sat on a round base of red bricks. Jixing was holding a bamboo tube in his left hand and slowly filling the tube with Jiāfú ashes (ashes made by burning the inner epidermis of reeds) with his right hand. On the bamboo tube, Chinese characters were engraved and painted pink: “Èryuè Jiāzhōng Qīngmíng” – Jiāzhōng (literally translated as “clip clock”) is one of the twelve temperaments of Chinese classical music while Qīngmíng (literally translated as “pristine and bright”), often falling on the fourth or fifth of April, is one of the twenty-four solar terms on the Chinese lunar calendar and also the time for Chinese people to have family reunions and worship their ancestors. All the bystanders held their breaths, for fear that any noticeable movements would spill the ashes and waste their efforts of collecting the reed epidermis in the past five days. When all the ashes were filled into the tube, Jixing knelt on the ground, leaning into the installation through its opening, and inserted the bamboo tube inside into the soil, lining up it with other bamboo sticks of different lengths. Then, he adjusted the position of the surveillance camera set on the side to make sure it could capture each of the bamboo sticks. After finishing all these, Jixing felt his body was in extreme tensity.

|

|

|

“A-lla-la-lei”

|

This installation project titled Qi-mometer (literally translated as “The Chamber Waiting for Qi”) was initiated by artist Petra Johnson and built together by several resident artists at Lijiang Studio and other local practitioners. It constitutes a part of the program “A-lla-la-lei” that explores the relationship between agriculture and art. While modern technologies allow for the use of soil thermometers to identify whether the soil is ready for seed planting, in ancient times, the task was accomplished by monitoring the alternation of the twenty-four solar terms of the Chinese lunar calendar. The Qi-mometer is a long-lost tool for monitoring the solar terms: the bamboo tubes of various lengths stuck in the soil inside the Qi-mometer are the pitch pipes, namely equipment for identifying pitch. These pipes are arranged in the Qi-mometer following the order of the twelve classic temperaments and buried in the ground with their positions aligned with the twelve two-hour divisions of the day. The solar terms are defined by the Sun’s position on the ecliptic. Meanwhile, as the Dì Qì (literally translated as telluric effluvium) ascends and descends at moments when the solar terms alternate, it also thrusts Jiāfú ashes out of the bamboo pipes.

The complete methods of operating the Qi-mometer and the effectiveness of the device can only remain a mystery. Yet the Internet and textual records that the practitioners found have laid a foundation for them to reimagine this two-thousand-year-old technology, explore local knowledge, perceive the environment, among other interests. The structural design of the Qi-mometer was created by resident architect Wu Shuyin, who referenced textual documents as well as the size and proportion of the haystack found in the village. The bamboos were collected together by the practitioners led by the studio coordinators, Er Ge and Xuemei. Then, there were local masters of fishnet and basket weaving, He Zhiqin and He Zhenjin, who taught the group how to weave with bamboo strips. Meanwhile, Katika Mediani (animation artist), Duskin Drum (artist and educator), Bochay Drum (landscape archeologist), Ben Torpey (farmer), and Xu Zhifeng (architect/artist) also sweat a lot for the construction of the Qi-mometer. A group of high school students from the US helped to rain-proof the structure with a coat of mud and built a path to it. According to feng shui master Mu Zongpei’s advice, the Qi-mometer should sit on a field with an unobstructed view, where one can see the magnificent scenery of the sun rising from behind the mountains. Accordingly, the practitioners decided to build the Qi-mometer outside the kitchen of the studio, where the family vegetable plot abutted the farmland that led towards the continuous mountain ranges afar.

|

|

|

“A-lla-la-lei” |

|

|

|

“A-lla-la-lei” |

|

|

|

“A-lla-la-lei”

|

|

|

|

“A-lla-la-lei”

|

|

|

|

“A-lla-la-lei”

|

|

|

|

“A-lla-la-lei” |

In the Naxi language, “A-lla-la-lei” means “how are you.” As a long-term resident practitioner, Petra began organizing the project in October 2018 by inviting the previous resident artist to join in and recruiting participants through open applications. Within over a year that began with the construction of the Qi-mometer, the project documented ecological knowledge and explored the mutual influence as well as co-generation of knowledge and perceptions under the framework of the solar terms. For example, when Petra repeatedly walked by the same route and documented the processes, she was both recording the changes of the view and creating new senses of time: “When I walk alone, the rhythms of the willow branches swinging would overlay the movements of my footsteps, and the symphony differed in different periods of the year, which also affected how I remember the scene. Such memories cannot be captured by the way how conventional calendar records time.” When walking with others, Petra would pay more attention to listening and the sharing of experience. This cycle of repetition and continuous tracing of experience demonstrated a way of manifesting the “surrounding” through itself on oneself: “No matter what we do, we are just trying to better foreground the richness of things that have been appearing and growing around us – and we need to make every effort to achieve this.”

As the project unfolds, it now also includes tasks such as growing vegetable, documenting the changes of vegetation within the village as the seasons alternate, observing the management of agricultural production of the village (for example, the management of canals and the timeslot for water releasement from the reservoir), and studying folk arts related to agriculture (which currently involves a plan to investigate a local song about farming). At the same time, the practitioners are also continuously organizing events such as film screenings and interactive activities presented on the weekly market held by the peasants, with the hope to create opportunities for mutual learning between local farmers and themselves.

A-lla-la-lei: On the Last Day of the Time of Greater Snow

Video | 8′30″ | 2020 | Courtesy of Petra Johnson

The videos are made of an assortment of 12sec recordings taken during the walks. This piece was edited from the footages shot during the solar term Dàxuě (literally translated as the “Greater Snow”) from December 7 to 21 in 2019, with Petra’s narration as the voice-over. Repeated walking, rhythms of the interlacement of the imageries – the solar term has framed the forms of being and perceptions while providing numerous derivative texts that are sometimes explicit and sometimes obscure, thus increasing the viewers’ sensitivity to the variations of “clarity”… The video drew its inspiration from the lunisolar calendar that exists in the form of songs in Naxi culture. Meanwhile, two other elements also greatly influenced Petra’s narrative strategy – the works of anthropologist Erik Mueggler and rituals performed by the young Dongba, He Xiudong. The video is also released in a version narrated in the Naxi language.

|

|

“A-lla-la-lei” |

|

|

“A-lla-la-lei” |

|

|

“A-lla-la-lei” |

During the course of the project, the participants decide what issues or directions they will look into. For instance, Jixing, one coordinator of Lijiang Studio, takes an interest in the relationship between the technique of monitoring Qi and music. He is curious about how the earth makes sounds through the bamboo pipes and expresses its wills. Zhu Ming, who moved from the city to the nearby village of Zhengsheng a few years ago, cares about local agricultural knowledge. He has persistently documented his observations on the phenomena and material realities pertaining to the four seasons and is accordingly eager to join the project to explore the possibilities of opening more perceptive channels. Thus, the purpose of perfecting and maintaining the Qi-mometer is not so much to obtain reliable, scientific outcomes as it is to advance a journey that helps coordinate the individual participants’ perceptions and connect their varied perspectives. In this process, the artists are also reflecting: how the wisdom and somatic experience of the countryside can be digested and regenerated in urban settings?

The practitioners in Jixiang Village have also formed a communal body with the practitioners from the nearby villages of Zhengsheng and Ciman, who would meet them to communicate about their works regularly. Many people within this community have been devoted to the discovery and cultivation of regional knowledge for many years. By learning about the ecological conditions in different contexts, they hope to explore how local experiences may transform the external experiences, which may make their communication with the villagers more efficient and help to reflect the villagers’ experiences to the outside world.

|

|

“A-lla-la-lei” |

“…Therefore, those concerned with tradition start with distortion. The young people who would learn the recipes of their grandmothers, and who regard the value of the soil with more than its speculative appraisal, are changing a direction, distorting a momentum that has naturalized into ta societal consensus … the Distortion of Distortion project investigated the skills and practices that hadn’t necessarily been written down, but that have been carried in the weathered hands and earthy wisdom of the people of Lashihai. However, writing these down is itself a kind of distortion of customs passed on orally or through gesture. So distortion goes a step further, and invents possible origins that defy origin.”

–––Excerpt from “Distortion of Distortion Recipes - Introduction”

In this project, the artists are concerned about the wisdom and the myths that have emerged in the farmers’ hands, the convergence of the local and the imported, and the alert against and reflection on how traditions are being observed and adapted – including also the gazing and adaptation of the artists themselves.

Emi Uemura and Michael Eddy have been carrying out food and farming practices for many years. From 2008 to 2013, they co-organized with others “HomeShop” ,a storefront space located in a hutong in downtown Beijing where they initiated many activities related to the issue of food and farming. The members of HomeShop often bring nomadic plants back to the space and built a garden there with local materials found on the spot. Emi Uemura and Micheal Eddy found that urbanites’ knowledge of the countryside tended to be acquired from flowing populations and the practice of planting transplantation. Apart from planting, composting, and organizing communication and exchange activities at the kitchen of HomeShop, Emi Uemura also initiated the “Beijing Farmers’ Market and Country Fair,” which offers an opportunity for small and medium farming households who practicing organic farming to communicate directly with consumers. Though the event started as an art project, it is currently kept running by a group of co-organizers including artists, farmers, farms, volunteers, consumers, and scholars. Through activities such as regular market fairs, farm visits, and sharing sessions, the event helps the farmers to widen their marketing channels, reduce the potential pollution brought by chemical fertilizers and pesticides, secure food safety, and realize fair trades. Emi Uemura and Michael Eddy also invited artists to participate in a series of art projects as the market fair attenders. All these artistic initiatives related to agriculture as well as food production and consumption have been continuously documented, complied, and displayed on the website “Hello, Vegetable! Have you eaten yet?”

In 2014, Emi Uemura and Michael Eddy came to Lijiang Studio, where they joined Julia Feyrer, Carson Fox, Marc Schepens, Mu Yun Bai, Jay Brown and others to learn from Er Ge and his family all kinds of ways to make food and the stories behind food like rice wine, spicy sauce for stinky tofu, and pickled vegetables, among others. The group also experimented with recipes collected from other regions, on which basis they made prints and a handmade book out of the stories behind.

For the artists, the decision to use the book as the medium came rather naturally. The “recipe book” is a down-to-earth vehicle of communication. Moreover, bookmaking is also a continuation of the artists’ previous experiences at HomeShop, where they rendered the book a means of social production that could endow the contents it carried with certain values. This means that the book is a suitable means of preserving the skills and practices that have not been systematically documented during their gradually lost in the transformation of agricultural business. When the either-real-or-fictional stories behind food are unfolded by the book, a sense of authenticity and ceremony emerges. At the same time, the book does not deny the distortion necessarily brought by the transience of its stay and the inadequacy of its delivery.

The project also catalyzed the dialogues among the “new farmers” by comparing the similar circumstances faced by different regions. Emi Uemura invited Japanese “new farmers” who see farming as a cultural and activist practice to Jixiang Village and Wumu Village nearby the Jinsha River. One of the farmers had spent ten years planting trees to bring a barren mountain back to life through the natural process. The project participants also watched together a documentary about a community farming society active in Tokyo in the 1970s.

Looking back at his practices in Beijing and Lijiang, Michael Eddy made the following reflection:

“Food circulates in entirely different ways in Lijiang and Beijing. In Beijing, the emerging middle-class families tend to see weekly engagement in farming as a joyful, wholesome lifestyle. However, young people of Naxi today are not necessarily interested in traditional agricultural, cultural, or religious practices. Moreover, nowadays, villagers living around Lashi Lake can no longer support themselves by acquiring their daily needs through farming. Despite this situation, there is still plenty to learn from the ways Naxi people prepare food, the structure of their houses, and their relationships with livestock.”

|

|

“Distortion of Distortion Recipe Book” |

|

|

“Distortion of Distortion Recipe Book” |

|

|

“Distortion of Distortion Recipe Book” |

|

|

“Qilin Dance” |

Amidst the sounds of gongs, drums, and suonas, the god Apu appeared with kaleidoscopic clouds.

The god holds a hossu in his hand and speaks auspicious words which generally means that though heaven is rather good, he sometimes feels lonely and thus wishes to visit the earth from time to time.

After going around the stage several times, the god exists the scene with the colorful cloud while two mottled ponies galloping forward onto the stage. The ponies jumped back and forth on the stage, full of vitality and effervescence.

Then the deer has also come down from the hill and frolic with the crane. They jump up onto the table one after another, alive and kicking, and bow to the audience in all directions. After a while, the crane even lays an egg!

Meanwhile, the phoenix accompanying the Qilin flaps its wings.

The god, divine animals, and the animals on earth walk together on the land of the human world, observing.

At this moment, the herder finds that the yak is about to give birth to its baby yak. He then brings the yak to the nearest village. After anxiously waiting, the yak smoothly gives birth and everyone sends their auspicious blessing.

Qilin Dance is a traditional activity of Naxi people that combines dancing, drama, and other art forms. It was originally introduced from Zhongyuan (the Central Plain) and has been gradually popularized among the folks after being adapted by several generations of Naxi people in the Ming and Qing dynasties. Only very few textual documentations of Qilin Dance have remained – local chronicles have only slightly touched upon the practice while the variations of the dance that have been passed down to this day are mainly circulated by word of mouth. Among the elderly, different people would tell different stories of the dance. It is said that Qilin Dance performed in Lashi Lake region originally came from Changshui Village adjacent to Ciman Village and has undergone a circulatory process of adaptation and cultural integration. When the dance is performed, gods, humans, secular and divine animals rejoice together to wish the coming year favorable weathers, bumper harvests, and a wonderful prospect of all things living in harmony. In the past, as long as the weathers were good for farming or a family had a joyous event to share, the villagers would stage Qilin Dance together to celebrate. When people and animals get sick, they would dance to ward out the evil spirits. In the Lashi Lake region, it is also said that Qilin can bring children. Therefore, when married people cannot conceive babies, they may invite Qilin Dance performers to their homes and walk around their rooms. Qilin Dance involves an improvisational part each time it is performed as the god would say different auspicious words according to various occasions.

As the tradition of Qilin Dance has been fading in recent years, no performance has been staged in Lashi Lake since 2004. Since 2014, after Wang Yicheng, a resident artist at Lijiang Studio, and Jixing, one coordinator of the studio, made an initiation together, several resident artists and a retired veteran Qilin Dance teacher, Mu Zongpei, have been collaborating to hold training workshops for the young people in the village, hoping to revitalize the tradition of Qilin Dance performance.

|

|

“Qilin Dance” |

The version of Qilin Dance practiced by the crew in southern Lashi Lake is relatively complete compared to others in Lijiang. It consists of six scenes including, following the sequence of the performance, “Birthday Congratulates from the Star of Old Age,” “Emergence of the Kaleidoscopic Clouds from the South,” “Herald of Spring by the Mottled Horse,” “Spring Union of the Crane and the Deer,” “Prosperity Brought by the Qilin and the Phoenix,” and “Auspiciousness Offered by the Yak.” When the teacher gives lessons on the dance, he only provides a general framework for the performance, leaving the performers to freely express the animal characters according to their understanding. Accordingly, different people may present the same dance in different ways.

|

|

““Qilin Dance” |

““Qilin Dance” |

|

|

“Qilin Dance” |

|

|

““Qilin Dance” |

|

|

“Qilin Dance” |

|

|

|

|

|

“Qilin Dance” |

|

|

“Qilin Dance” |

During the performances, the dancers move around the stage and fully activate the playing area. When the stage is large, the range of their movement will be wide; when the venue is small, activities will be carried out within a limited area. By moving back and forth on the stage, the performers create a sense of spatiality. There is no clear boundary between the playing area of Qilin Dance and the seating space, which allows the dancers to interact with the audiences from time to time. Correspondingly, the audience needs not to seat still – they can walk around at will. Only in this way may the audience have a holistic viewing experience of the performance.

|

|

“Qilin Dance” |

|

|

“Qilin Dance” |

|

|

“Qilin Dance” |

The performance of Qilin Dance contains the relationship between humans and animals, between gods and animals, as well as between humans and heaven. It is closely related to the worship of nature and animals in Naxi culture. At first, this area was dominated by nomadic culture and pastoral economies, which gradually converged with farming culture. Animals such as Yaks and horses stay close to the people there. The traditional dances in Naxi culture include many animal elements; meanwhile, the gods in the Naxi culture often appear in the image of one animal or a combination of several animals, which demonstrates the worship of various qualities of animals such as strength, fertility, courage, and self-healing power, among others. In Naxi mythology, the gods of nature who oversee mountains, rivers, flowers, grasses, and trees are the half-brothers who share the same father with the humans who manage the farmlands and livestock. Later, humans’ greed destroyed nature and incurred punishment on themselves. Dongba thus summoned the gods to intermediate and establish a contract between humans and nature: men can use natural resources, but not excessively; they should not hunt and kill animals unrestrictedly, or cause pollutions to the environment. To show gratitude and compensate for their sins, humans need to continuously perform rituals. Dancing is considered a way of balancing the human society and the mysterious world of nature – it approaches deities through anthropomorphized representations of gods, imitations of the animals reared by gods, and impersonations of the animals being worshiped. Dancing tells the stories of survival, expresses joyfulness, and experiences euphoria and aesthetic perceptions through nature itself and movements of the dance. It also helps to socialize and obtain the goal of entertaining both humans and gods. After the success of Qilin Dance performance in 2014, Jixiang village established the “Qilin Dance” crew that has been since active on many important occasions within and outside of the village. Local practitioners and resident artists are also learning to making props for the dance and exploring how to experimentally combine the performance with other art forms.

Image and video courtesy of the artists. All rights reserved.