Born in 1976, Mao Chenyu came from Ximaojia Wū Chǎng (a type of small village usually established on the settlement of the same clan; commonly seen in Southern China) in Songyuan Village, Xinqiang Town, Yueyang City, Hunan Province. His practice of image and film production started after he completed his studies in inorganic non-metallic materials in the School of Materials Science and Engineering, at Tongji University in 2000. Paddy Film is a series of video experiments initiated by Mao Chenyu in 2003. The series mainly adopts ethnographies as the film texts, focusing on issues including subjective experience and perceptions that are often overshadowed, rural narratives and languages, the differences between ethnic groups, and the politics of land and earth, among others. It involves shootings in the paddy fields in areas extending from the vicinity of Yueyang City in Hunan to Shennongjia Forestry District in Hubei and some major regions surrounding Dongting Lake like northeast Guizhou. Through these, the series touches upon topics including the cultures, agricultures, and social relations concerned with the practice of paddy growing, manifesting the will of being and the genealogy of spirituality contained in such practice. Since 2013, the artist has also developed new language systems through related events such as exhibitions, lectures, interdisciplinary collaborations, among other media.

To establish a corporeal relationship between Paddy Film and paddy growing, Mao Chenyu started a farming practice in his hometown in Ximaojia Wū Chǎng, where only a dozen households, consisting of around thirty people, are currently living. Almost all the youngsters there have left the village to work outside due to the low profitability of farming, just like in most rural villages of China today. In the village, highly toxic pesticides are widely adopted; in the surrounding area, many factories are also emitting toxic substances. In 2012, Mao Chenyu came back to Ximaojia Wū Chǎng and contracted thirty acres of farmland, on which he applied no chemical fertilizers but only tea seed saponin to exterminate insects. Mao has also delimited a part of the land as non-agricultural areas to provide a resting place for frogs and other creatures during farming periods. In addition to his personal, domestic farming practices, Mao Chenyu encourages his neighboring villagers to experiment with ecological planting methods. Through demonstrating the actual profits made, he tries to gain the villagers’ recognition and persuade them to transfer their paddy lands to Mao’s family for paddy growing, soil amelioration, and the construction of the large-scale ecological agricultural blocks. All these trials had developed into a contestation with the State’s compulsory planning and management of rural spaces, which were carried out at the same time, and finally failed to compete with the latter. In 2017, other villagers in Ximaojia Wū Chǎng gave up on ecological farming while Mao Chenyu carried on with the practice and inherited his father’s occupation as a winemaker. For Mao, these changes have strengthened the functionality of Paddy Film Farm and led to new routes for narration. Placing farming practice as the core of his work, the artist then initiated a series of research and public education events in the rural, organizing for the villagers to learn agricultural knowledge to improve the local ecosystem. Meanwhile, he adopts visual media to document the everyday orders as well as the constraints and counterstrategies manifested in farming and social ecologies. The individual’s farming practice thus not only produced food but also generates grassroots organizations and social relations, providing a long-term, situated coordinate for Paddy Film to writing about political stances, cultural actions, and ecological issues.

“Paddy Film" presents rice paddies as the characterization and a catalyst of culture in the public domain. It tries to establish open-ended dialogues with other media through visual and textual communications. In doing so, it intends to update the genealogy of rural knowledge and develop the vocabularies for the articulation of rural experiences:

As I have been working in rural societies for long, I pay special attention to the divinity of rural life. That is to say, in what we call the secrete rural societies of China, what are the thoughts and the fundamental mentality that the farmers rely on to accomplish their representations in the world? The system of cultural production in which we are situated is essentially a contemporary, urban one; in other words, the so-called cultural production that we are now talking about, one of the experiences and knowledge of rural societies, has been gradually screened out by contemporary society. Even we can still see the existence of towns and villages today, what we see is only the presence of the rural produced by the mass media and the artists whose subjectivities played a dominant role in such production. In such case, how can the subjectivities of the local farmers or the situated, local experiences find an effective way to free themselves from the muteness and release themselves on a platform for contemporary knowledge production?This is the issue that I came to realize in 2012, and it hints on some new possibilities (for my query).

——Excerpt from “A Dialogue about Paddy Film Farm” ,published on the public WeChat account of Paddy Film Farm on November 2, 2016

The artist sees film making as a driving momentum and constantly breaks away from the conventions of cinematic discourses to disturb the inertia of cognition. For example, in a series of documentary practices that he terms as “second text writing,” Mao tries to minimize the rhetoric, emphasize the subjectivity of his subject, and expunge the presence of the author. In this way, he intends to highlight local contexts from an inner, closed perspective rather than an external, spectatorial view. However, since 2013, Mao has reserved in his practices a place for personal experiences and perspective. Adopting a “to-be-determined” mode of thinking, he often continuously edit the same piece of audio-visual material and revisit the traces as well as the courses of its making. During this process, he also constantly cross-references his existing works. Overall, the artist adopts ethnography as both a method and a style to explore the dynamic relationship between fieldwork experience and theorization while striving to introduce other-than-human perspectives into film production.

Since 2003, I have personally experienced the historical progression of ethnography as a literary form – from the patronizing (colonialism), the hypothetical based on an assumed construction of certain relationships (fabricated situations), and the writing of the “self” by its representation (simulacrum) to the one that manifests the internal relations of writing (engagement) and the authentic writing of the self (subjectivity). When “the other” I deal with my work constantly shifts its position, I am faced with the issue of “the othering of the self.” Here, how the “self” can be decomposed and dislodged from its social attributes and the connotations of the concept “human” has become the crux of my handling of the act of “writing.”

——Excerpt from “Writing Society: Cinematic Ethnography” published on the public WeChat account of Paddy Film Farm on December 5, 2015

Paddy Film series

Ximaojia Universe

Film | 78' | 2013

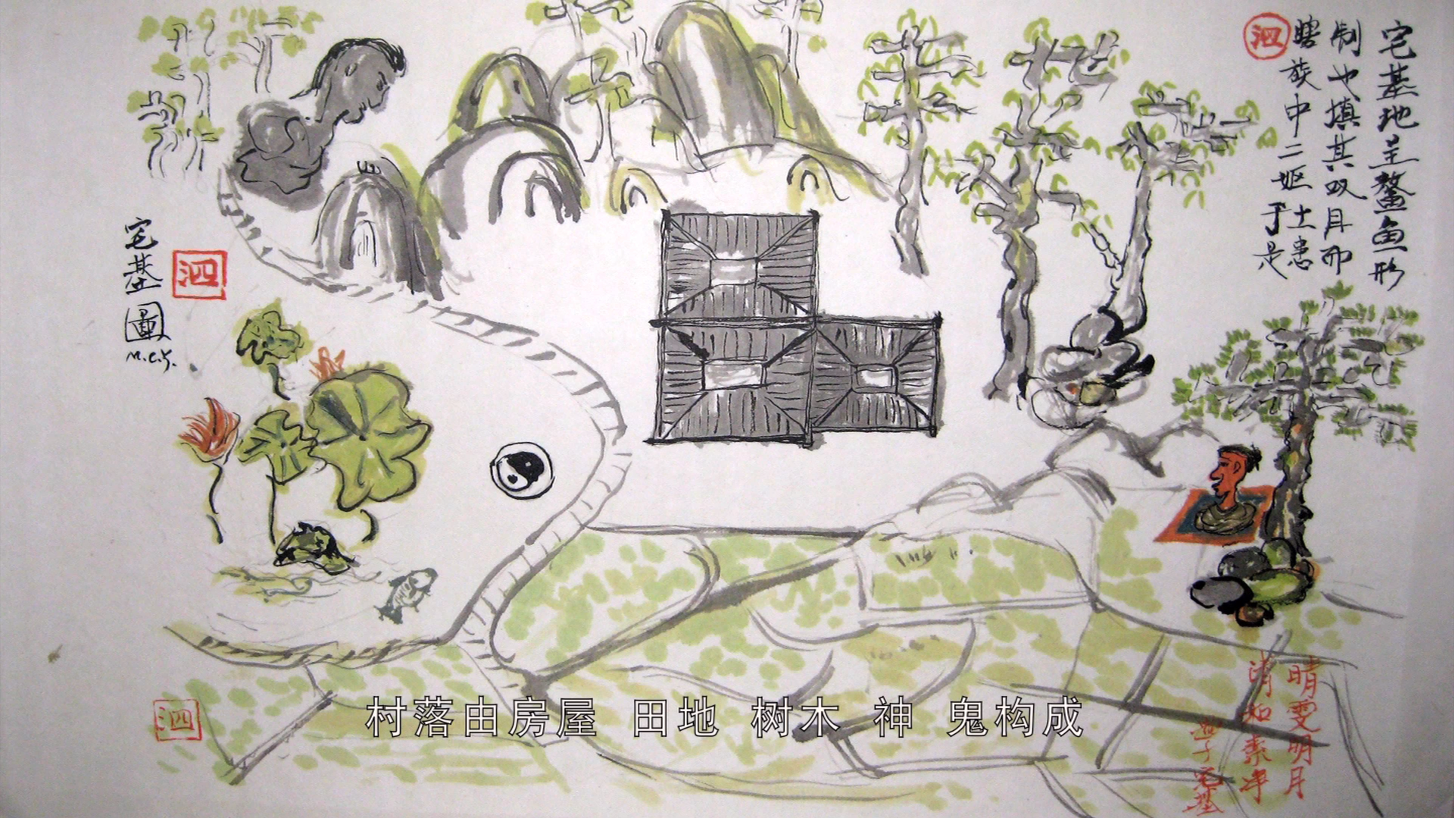

The artist returned to his hometown, where he joined the community life of his clan. As a community member and an ethnographer, he conducted an archeological investigation of the Ximaojia (Ximao clan) consisting of only eleven households and a little more than twenty people. In this way, he explored the intrinsic messages contained in the life of the clan, writing down its histories and myths. Meanwhile, he created several categories of objects and placed them in the clan. In doing so, he attempted to investigate the particular meanings generated by the objects in the context of clan life and the cosmologies they corresponded to. The film, by annotating the position occupied by the artist, attempts to construct a historical-mythological genealogy of a commonplace village. In doing so, it tried to make the film happen to the village historically.

Paddy Film series

I Have What? Chinese Peasants War: The Rhetoric to Justice

Film | 103' | 2013

The essay film I Have What? Chinese Peasants War: The Rhetoric to Justice examines China’s agricultural discourses and the status of capital in the past several decades through regional samples. It investigates issues including how the land system may acquire equality and efficiency as well as the loss of divinity in the relationship between the peasants and the land. Meanwhile, the film also attempts to expand the vocabulary of the land and farming. As the artist was tracing the land and the relics of past beliefs, he also interviewed more than a hundred peasants in a dozen village communities (see “A Questionnaire About Chinese Grassroots’ Needs – Yueyang Volume”). In front of the camera, the peasants either soliloquized or sit by one another to discuss current social affairs, their hypotheses of things, and anticipations, thus re-sharpening certain concepts that had once become inertia thinking through personalized expressions of emotions and narratives. The film also discusses the relationship between introduced species and the severe drought in Yunnan-Guizhou Plateau as well as the changes in the “rationality” of local governance.

|

Paddy Film series

Cloud Explosion, Dongting Lake and the Death of Its Symbols

Film | 78' | 2015

|

The Yueyang City Finless Porpoise Conservation Association is a non-government organization. However, the chairman of the organization in 2012 was Xu Yaping, a chief on-the-scene reporter of a party organ. In the experimental film Cloud Explosion, Dongting Lake and the Death of Its Symbols, Mao Chenyu conducted a syntactical analysis and deconstructed the contents Xu Yaping posted on Weibo. In doing so, the artist discussed in the film how environmental protection has become a discourse that can be easily appropriated for self-promotion and criticized the society’s worship of unnatural powers through editing the found materials from the Internet. In the film, Mao juxtaposed the splendid sceneries extracted from the promotion videos made to attract investments for Yueyang City with the scenes of ecological degradation. Accompanying that, he blended music popularized on the Internet and local operas. The film adopts a visual style similar to that of slideshows, using elements such as bold texts, letters of changing colors, underscores, and animated graphs, which may make the viewers at loss at first. However, this visual strategy makes a clear statement: nothing that contradicts in reality cannot be integrated on the level of the medium, while techne – including the rhetoric – necessarily determines the shape of justice and the future. “Dongting” has become a symbol.

|

Paddy Film series

Global Grammar

Video | 11'27" | 2015

A veteran hunter in Shennongjia Forestry District who believes that a tree in the village is the center of the world. As he sees it, Yěrén (literally translated as the wild man), rather than being an unknown species, is a mode of existence for the dead or telepathy belonging to the human.

|

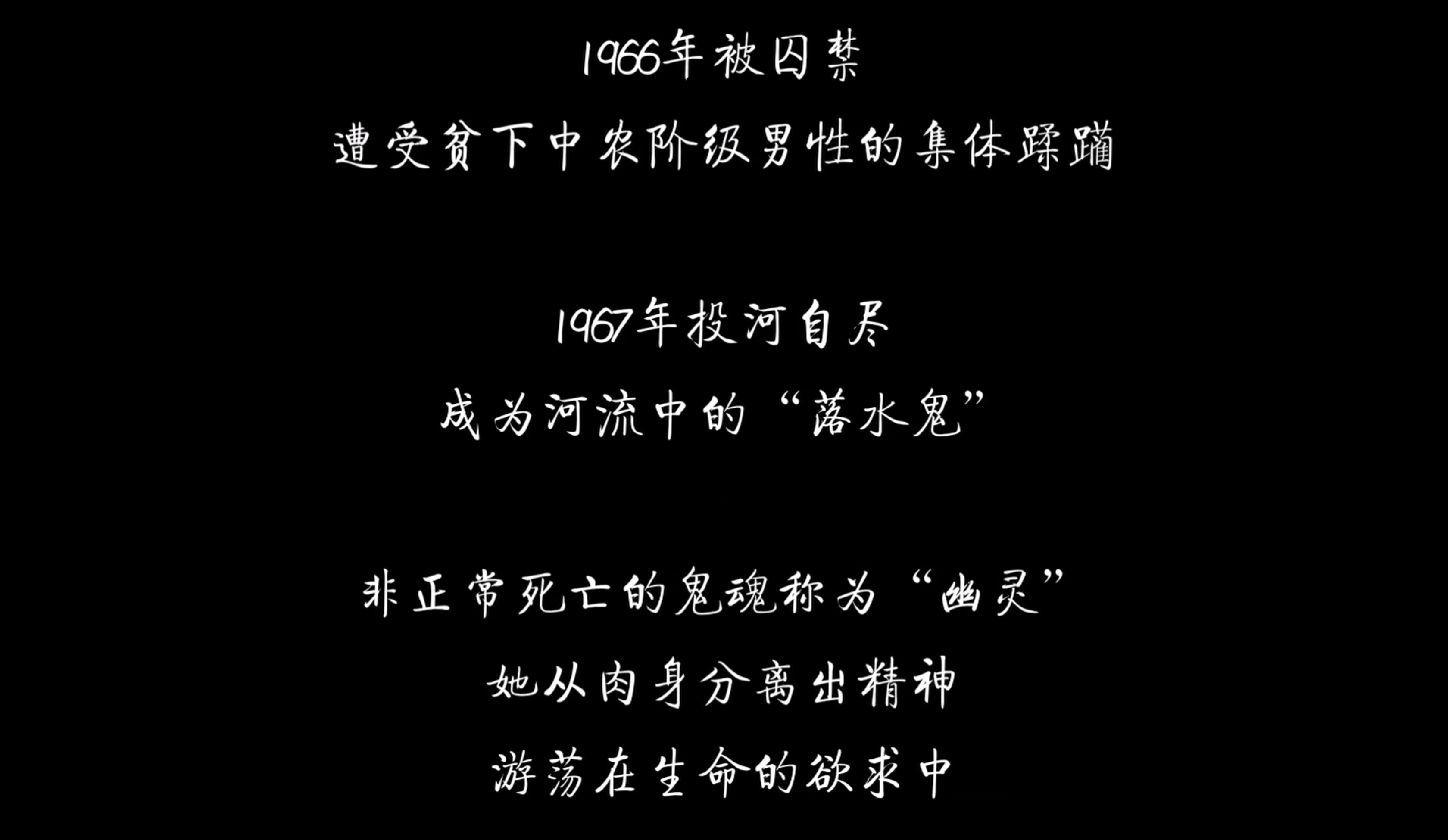

Litchi Girl is an alias of a woman living in the Dongting Lake basin. Her story is only circulated among people by word of mouth. Born in 1920, she joined the frontline medical team in the Battle of Changsha during the Second World War and committed suicide by jumping into a river in 1967 after being insulted. Mao Chenyu created an array of moving image works, installations, and exhibitions revolving around this folk character, through which he attempted at not excavating historical facts but searching for the hidden mechanism of narrative production, creating an open framework for reading, freeing the character from existing narrative structures, representational networks, and labels, and thus turning Litchi Girl into “an interface for media practices that are both substantial and unverifiable”:

“My mixed-media installation attempts at creating an image system that speaks about Litchi Girl’s being. I am searching for – in the genealogy of images in the eastern Dongting Lake basin in Hunan, China from the 1920s to 1967 – elements of the public and the local systems, the mobile and the forever static, the male and the female, the natural and the politically “fabricated” units of labor and division of production, as well as the space of politics, the territory of morality, and the ethical boundaries among sexuality, sex organs, and sexual behaviors. Even, I may create an archeological site at which excavation work can be carried out to unearth Litchi Girl’s death in the river – although her putrefied breasts and torso steeped in the water were salvaged in 1967, I wish to further investigate the geographical dimension of this site. Only the river constitutes the fundamental dimension of the human bodies – as the frontline of the Second Sino-Japanese War, as the running water that once washed the sexual organs, erotic passions, and sexual feelings, and as the drowning site of the 1967 incident, the river is permanently fixed in local geography. When people in 2016 raked the riverbed and panned gold from the sand to obtain the valuable substances, they were also working according to the geographical dimension of the river … For constructing this genealogy of images, the primary task is to create the imagery of darkness – a pedigree of darkness that I have sensed from the politics and poetics of the sand and gold in the river. And then, at the drowning site of Litchi Girl, I will excavate the thin and brittle layer of sandstone, and perhaps the ebony and the sands containing gold too. Thirdly, I plan to produce a documentary film about the current village in which Litchi Girl once lived. It will be a query with those who have survived and interrogation on the people who collectively played the role of the killer. Lastly, (my work will involve) also the literature on which the story relies for existence and those images of nebulosity.”

——Excerpt from “Winter Solstice | The Body of Time: Story, Editing, Production,” published on the public WeChat account of Paddy Film Farm on December 21, 2016

|

Paddy Film series

Automatic Paddy

Video | 4'18" | 2018

“On one hand, we abalienate the discretionary powers over the selection of openly solicited plans; on the other hand, we need also to provide some suggestions on the plan like what kinds of infrastructure can potentially be reinstalled after we pass the ‘thin and brittle’ era of the Anthropocene.”

|

|

Paddy Film series

Nuoist Economy

Video | 14'50" | 2018

“Calling in some Taoist Imps, and then sending out some new one.” Nuoist Economy investigates the economy of Nuóxì (Nuo opera) through documenting the religious rituals practiced in southeast Guizhou province. It discusses issues including how people conceptualize gods, create gods, and understand ‘divinity’.”

|

Image and video courtesy of the artists. All rights reserved.