|

|

Villagers painted "Urban-Rural Coexistence" on a slight slope at the village entrance of Wang Chau. Photo by the research team. |

|

|

Villagers painted "Urban-Rural Coexistence" on a slight slope at the village entrance of Wang Chau. Photo by the research team. |

Wang Chau is located in Long Ping, Yuen Long, a green belt in the northwest of the New Territories. There are three villages in Wang Chau – Wing Ning Tsuen, Fung Chi Tsuen, and Yeung Uk San Tsuen. The entire Wang Chau incident had been complicated. To sum it up in the simplest way, it was a dispute between "New Territories rural leaders and non-indigenous inhabitants" and "greenfield site and brownfield site." In Wang Chau's Three Villages, both indigenous and non-indigenous residents have grown up here and lived in the villages for decades. If we visit Wang Chau today (2020), we would see that one side of this place is where the villagers live and farm (green-belt site), and on the other side are the open-air warehouses, mountain graves, and parking lots (brownfield site).

|

|

Walking up the mountain from the village entrance of Wang Chau, we saw a large brownfield used as a warehouse and the Shenzhen Bay. Photo by the research team. |

|

|

Walking up the mountain from the village entrance of Wang Chau, you would see many mountain graves built by the indigenous inhabitants occupying the green belt sites. Photo by the research team. |

According to government information, the planning intention of the green belt is primarily for “defining the limits of urban and suburban development areas by natural features and to contain urban sprawl as well as to provide passive recreational outlets. There is a general presumption against development within this zone.”

In 2012, Chief Executive Leung Chun-ying started rezoning green belts and country parks into residential land to increase housing supplies. The rezoning includes introducing the “Planning and Engineering Study for the Public Housing Development and Yuen Long Industrial Estate Extension at Wang Chau" . This project aims to develop 17,000 public housing units on 34 hectares of land. Before the rezoning, the government had repeatedly "Test the water (informal negotiations)" with Yuen Long rural leaders. At first, rural leaders opposed the development. Two years later, the government proposed to develop Phase 1 (development in green-belt site) first while deferring Phases 2 & 3 (development in brownfield site) (Remarks: Phase 2 has housing as well, and isn't all brownfield). And the problem started from here.

In September 2016, activist Eddie Chu Hoi-dick raised concerns about potential collusion between the Hong Kong government, businesses, rural landlords, and triads behind the entire Wang Chau incident. Eddie Chu criticized that the government developed the complete Wang Chau development plan based on the "green first and brown second" approach, which violated the principle of "brown first and green second" (that is, brownfield development first, and then greenfield). Some local media described the incident as the "Yuen Long Wang Chau dark scene," which was also the turning point of the whole incident.

After meeting with the rural leaders, the government decided to downsize the plan to build only 4,000 public housing units on 5.6 hectares of the green-belt site. The original plan to reclaim the brownfield site to build 13,000 units was deferred to Phases 2 & 3 without stating the development schedule, giving the public the impression that Phases 2 & 3 would be "indefinitely shelved." At the same time, non-indigenous residents living in Wang Chau had not received a formal eviction notice from the government. Still, the government had started to conduct a freezing survey in the village in 2015, leaving the villagers suddenly at a loss.

Faced with a series of threats to lose their homes, the villagers spontaneously formed the "Wang Chau Green Belt Development Concern Group". When the media reported the incident and gradually gained public attention, various supporters joined the concern group, including many artists. They intervened through different strategies to respond to the development and deliberately emphasized the Wang Chau Green Belt’s ecology through art festivals, publications, etc. The research team interviewed the villager Ms Cheng of the "Wang Chau Green Belt Development Concern Group" and artist Michael Leung to learn more about Wang Chau.

|

|

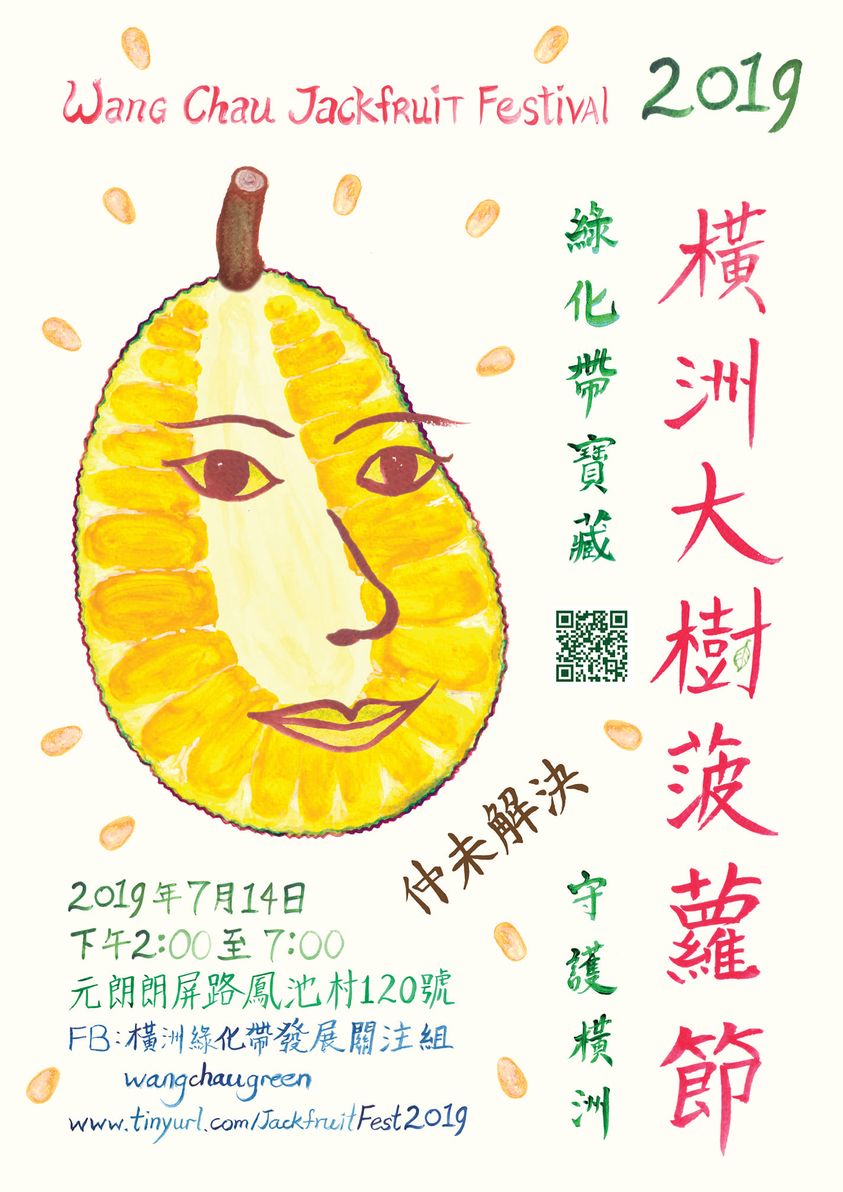

2017 Wang Chau Jackfruit Festival poster, designed by Michael Leung. (CC BY-NC 4.0) |

|

|

2017 Wang Chau Jackfruit Festival poster, designed by Michael Leung. (CC BY-NC 4.0)(CC BY-NC 4.0) |

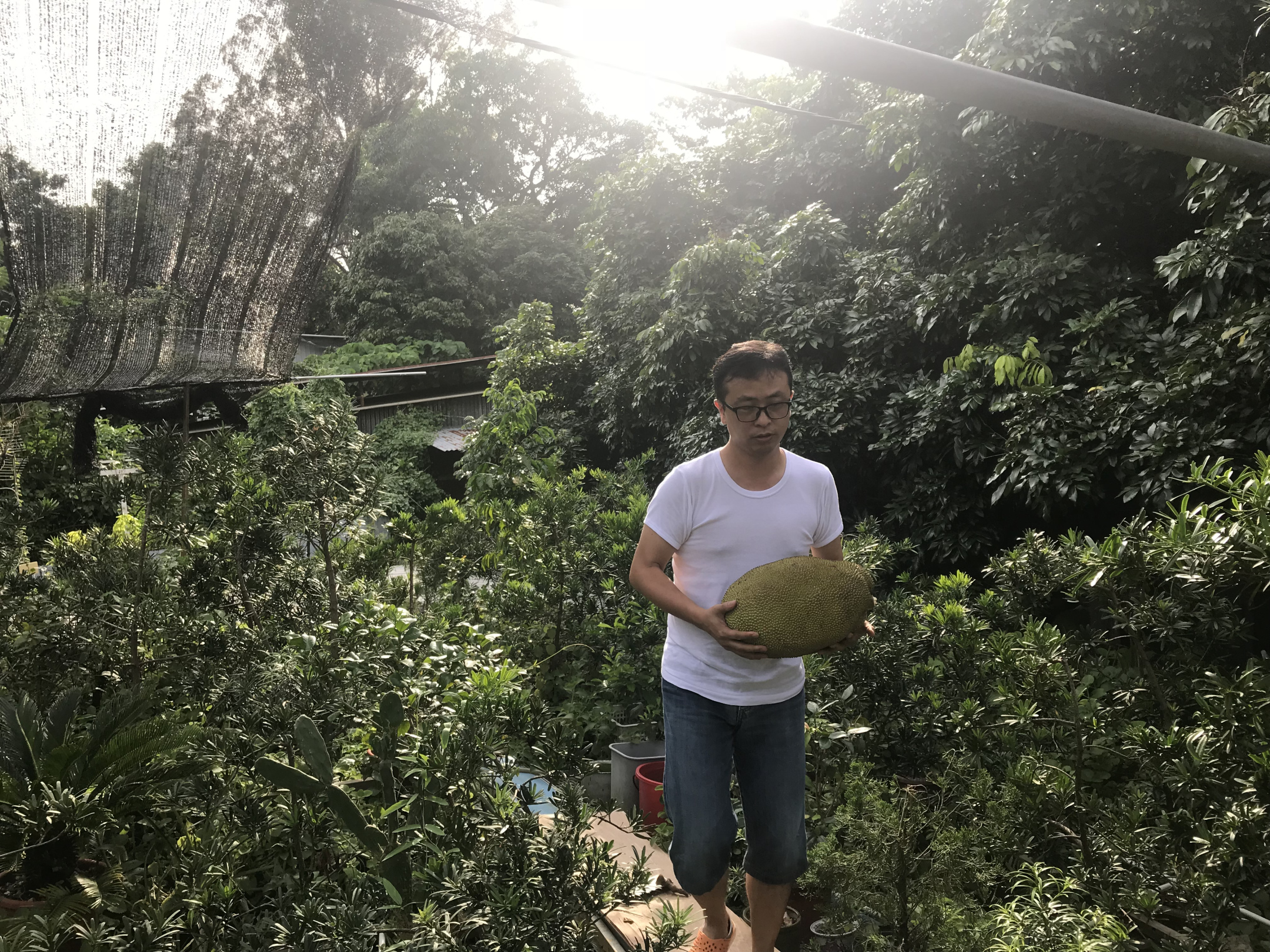

Wang Chau Jackfruit Festival was held for four consecutive years from 2017 to 2020. Each of the years, villagers shared the harvests of the Wang Chau greenbelt with the public through different jackfruit dishes, workshops, guided tours, a craft tent, and music concerts. But more importantly, they hoped to attract more people to the villages through the Jackfruit Festival to learn about the ecology of this green belt and the future it was facing.

“Every summer, these villages are inundated with the scent of jackfruit. The villagers have been the caretakers of the fertile greenbelt for generations. The jackfruit trees in the villages are thriving, and many have been there for decades. However, the government has ignored the value of the three villages as part of the greenbelt before pushing for the Wang Chau Public Housing Plan. The so-called Feasibility Research Papers completely bypassed the original principle of the planning by not mentioning a word on the impact of the ecosystem in the vicinity. Decimating the greenbelt is never simply about losing decades-old fruit trees, but more like losing an entire precious ecosystem. Recklessly giving the green light to such a plan without further studies on the long-term environmental impact and consultation with the locals is a cold, senseless decision that has brought irreversible damage to the inhabitants and natural life of the three villages.” This paragraph is the introduction to the Jackfruit Festival by the Concern Group.

|

|

The "2019 Wang Chau Jackfruit Festival" poster. Designed by Michael Leung with calligraphy by Lam On Ki. (CC BY-NC 4.0) |

Regarding the origin of the Jackfruit Festival, Michael Leung wrote in “The Emergence of the Jackfruit Woman”, “The Wang Chau villagers spoke about their small farms and gardens, and fruit trees—grown by their parents. Speaking about their tall jackfruit trees, this led to the idea of creating a 2017 Wang Chau Jackfruit Festival, an event that differed from the strategies employed by the villagers in the past year and a half—something welcoming, celebratory, and rich with stories—contributing to a creative resistance.” [1] And the jackfruit was given a gender by the concern group - the jackfruit is "she." Imagining the jackfruit as a woman was the group's response to the patriarchal laws of the entire countryside. In Hong Kong, the New Territories have long been dominated by men. For example, only male indigenous villagers have the right to build small houses in New Territories (according to Hong Kong’s New Territories Small House Policy). The group imagined the jackfruit as "someone fictional and an inclusive representative who cannot be intimidated by any village leader, rural council member, hostile rural strongmen or the government."[2] In the book, Michael Leung wrote, “Jackfruit Woman can perhaps speak for the disempowered villagers (all genders) and the multispecies living inside the green belt. She is someone who is physical and digital, omnipresent and invincible, across many geographies(...)”[3] The Jackfruit Woman

was also displayed in Para Site’s exhibition, “Soil and Stones, Souls and Songs, in the part of “A Tale: The Land of Fish and Rice” curated by Qu Chang.

The first Jackfruit Festival was held on July 23, 2017. Activities included a citizens’ alternative plan competition with the Wang Chau land issue hosted by architectural sector lawmaker Edward Yiu Chung-yim, a guided tour to share with the public the experience of rural life in Wang Chau, and workshops on making jackfruit jam, fragrance soap, and leaf vein bookmark, tents related to jackfruit by-products (non-commercial), and a music concert led by Wong Hin Yan, Peace Wong, & Teenage Riot. The first Jackfruit Festival had received mainstream media exposure, such as Oriental Daily News's interview.

|

|

2017 Wang Chau Jackfruit Festival. Photos courtesy of Wang Chau Green Belt Concern Group. |

|

|

2017 Wang Chau Jackfruit Festival. Photos courtesy of Wang Chau Green Belt Concern Group. |

|

|

2017 Wang Chau Jackfruit Festival. Photos courtesy of Wang Chau Green Belt Concern Group. |

|

|

2017 Wang Chau Jackfruit Festival. Photos courtesy of Wang Chau Green Belt Concern Group. |

The 2nd Jackfruit Festival was held on August 18, 2018. The activities included jackfruit tasting, workshops, guided tours, craft tents (non-commercial), a new book-sharing session, and live music performances. Among them, artist Ricky Yeung Sau Churk participated in the festival that year, leading the villagers and participants to write Chinese calligraphy with adhesive tape in Wang Chau.

The 2nd festival was also covered by different media, including The Stand News, which shared an article written by the Wang Chau Green Belt Development Concern Group, "Wang Chau Flower Language - When things are difficult to achieve, the iron tree blooms.". There was an old proverb of the Ming Dynasty, "Between Wu and Zhe, there is an old proverb that the iron tree blooms when things are difficult to achieve." It implies something difficult to achieve, as the iron tree is a kind of plant which does not flower easily. Concern Group wrote the feelings of the villagers towards Wang Chau in the article: “We, are heartbroken and sober because of the oppression. / We, emit fragrance because we are oppressed." [4]

In addition, Next Magazine also reported on the Jackfruit Festival under the headline "[The fruit scents that cannot be retained] The demolition of Wang Chau is coming, From the last harvest of jackfruit to look back on the joys and sorrows of the resistance.”, it describes the festival with a soft and sensational reporting method: "This year, Jackfruit Festival was held in the open space in front of the villager Ms Ng's house. Before the demolition, Ms Ng opened the nearly 50-year-old home to the public. A series of preparations and decorations have been made over the past few days. She got up early that day, and she was very busy after the festival started. After sunset, Ms Ng finally had time to eat the jackfruit and looked up at this piece of land."[5]. The independent media RadicalHK reported on this festival with the title "Leave the Seed, Goodbye Wang Chau Jackfruit Festival."

|

|

At the 2nd Jackfruit Festival in 2018, artist Ricky Yeung Sau Churk led the participants to write Chinese calligraphy in the village. Photo courtesy of Wang Chau Green Belt Development Concern Group. |

|

|

The Chinese calligraphy work by artist Ricky Yeung Sau Churk and the participants. Photo by the research team. |

|

|

Some artists made murals in the village. Photo by the research team. |

The 3rd Jackfruit Festival was held on July 14, 2019. At that time, due to the social movement in Hong Kong, the number of people participating was less than before. This year, only the independent media RadicalHK still reported on the Wang Chau Jackfruit Festival and published “Flowers Blooming Everywhere: The Daily Resistance: The 3rd Jackfruit Festival is held today", and it writes this festival from the perspective of the preparatory stage: "On the eve of the Jackfruit Festival, a group of villagers and volunteers worked hard to prepare. First, they turned the jackfruit into different dishes, such as Indonesian curry fried jackfruit, jackfruit icy drink, tri-color jackfruit icy drink (jackfruit icy drink with three-color water chestnut and coconut milk), and special jackfruit drinks, etc. The process is not simple at all. The reporter was lucky enough to participate in it because of the interview. Roughly speaking, the villagers have to collect jackfruits. First, the villagers are skillful and instantly obtain jackfruits from the trees. After boiling the jackfruits, a group of volunteers skillfully peeled the jackfruits and took out the jackfruits pulp, like female workers, and finally, they passed the jackfruits to the chef; for cooking."[6]

|

|

The 3rd Jackfruit Festival in 2019. Photos courtesy of RadicalHK. |

|

|

The 3rd Jackfruit Festival in 2019. Photos courtesy of RadicalHK. |

|

|

The 3rd Jackfruit Festival in 2019. Photos courtesy of RadicalHK. |

|

|

The 3rd Jackfruit Festival in 2019. Photos courtesy of RadicalHK. |

In addition to the Jackfruit Festival, the Wang Chau Green Belt Development Concern Group and its members have also extended Wang Chau's relationship with the public through publication.

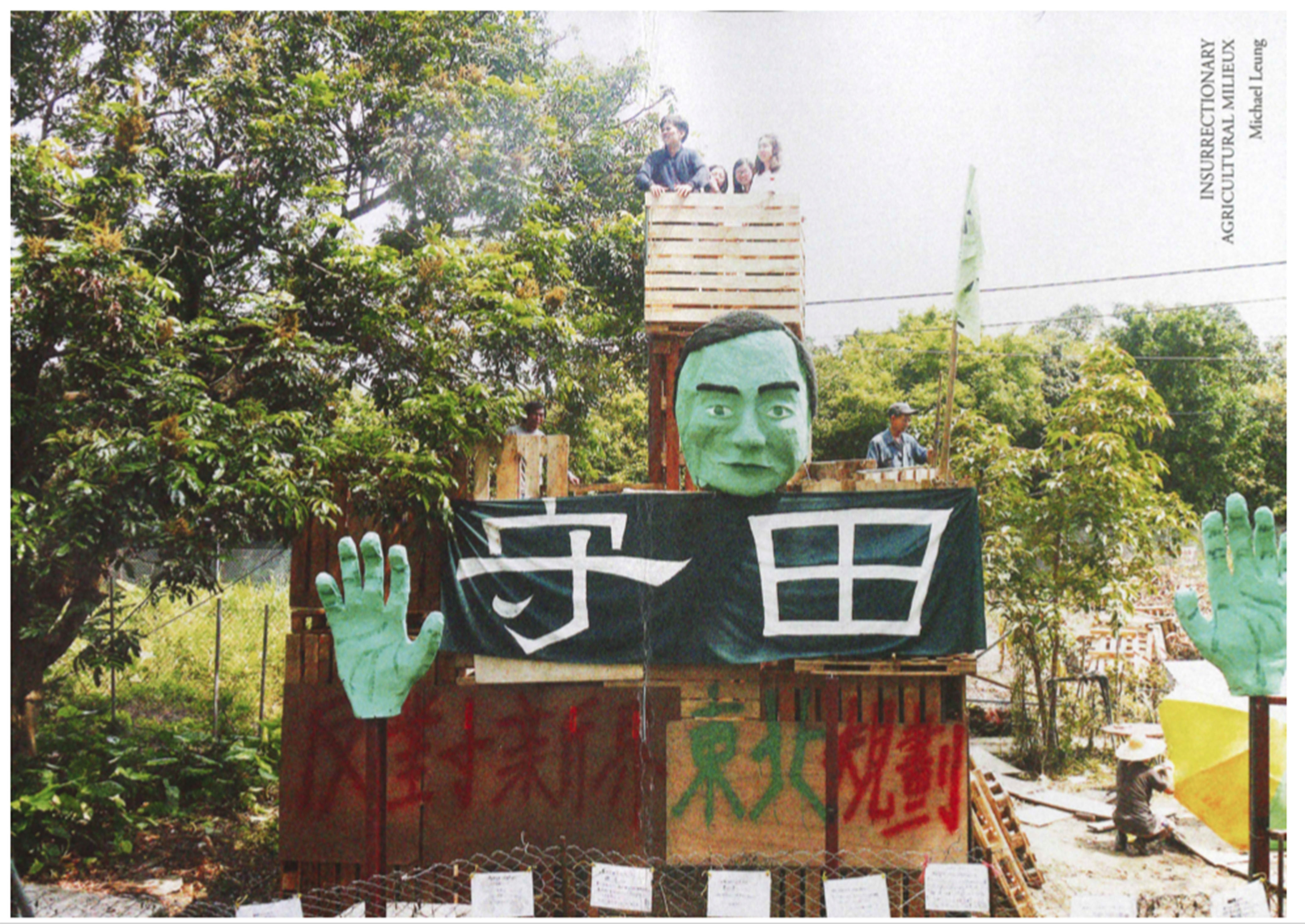

Artist Michael Leung published two independent publications: "Flowers (Soil and Stones, Souls and Songs): An Artist Statement" (2017), and "The Emergence of the Jackfruit Woman" (2019). "Insurrectionary Agricultural Milieux" puts the writer's experience in Wang Chau into the context of Hong Kong as a whole, thinking about the relationship between free-market capitalism and land. "Flowers (Soil and Stones, Souls and Songs): An Artist Statement" and the exhibition "Soil and Stones, Souls and Songs" at Para Site at that time became a "synchronous movement," echoing each other in different exhibition spaces and social spaces. "The Emergence of the Jackfruit Woman" re-examines the author's past actions in Wang Chau from a gender perspective.

|

|

Cover page of Michael Leung’s “Insurrectionary Agricultural Milieux.” (CC BY-NC 4.0) |

|

|

Cover page of Michael Leung’s “Flowers (Soil and Stones, Souls and Songs): An Artist Statement" (CC BY-NC 4.0) |

|

|

Cover page of Michael Leung’s "The Emergence of the Jackfruit Woman" (CC BY-NC 4.0) |

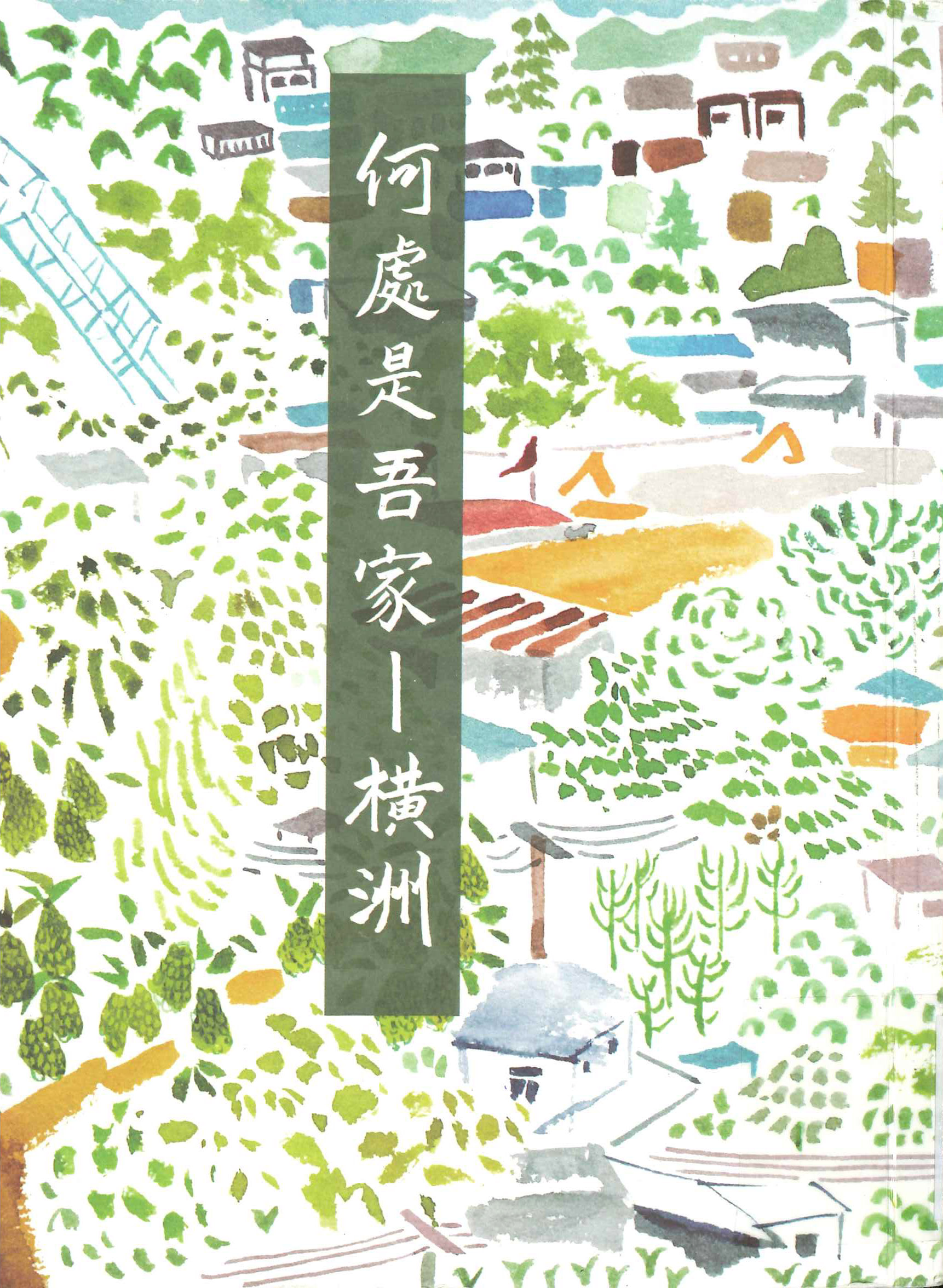

Moreover, the Wang Chau Green Belt Development Concern Group led by the Villagers also published "Where is My Home - Wang Chau" in 2018. The book records Wang Chau in a way that focuses on both emotions and rationale. It contains the part that records the feelings and lives of the villagers ("the feelings of the villagers"). The part that looks at Wang Chau from the perspective of professional planning and sociology ("the civil affairs of the village"). The part from the historical point of view ("the history of Wang Chau"). And the part that reflects the possible follow-up reflection on the movement (“after the resistance").

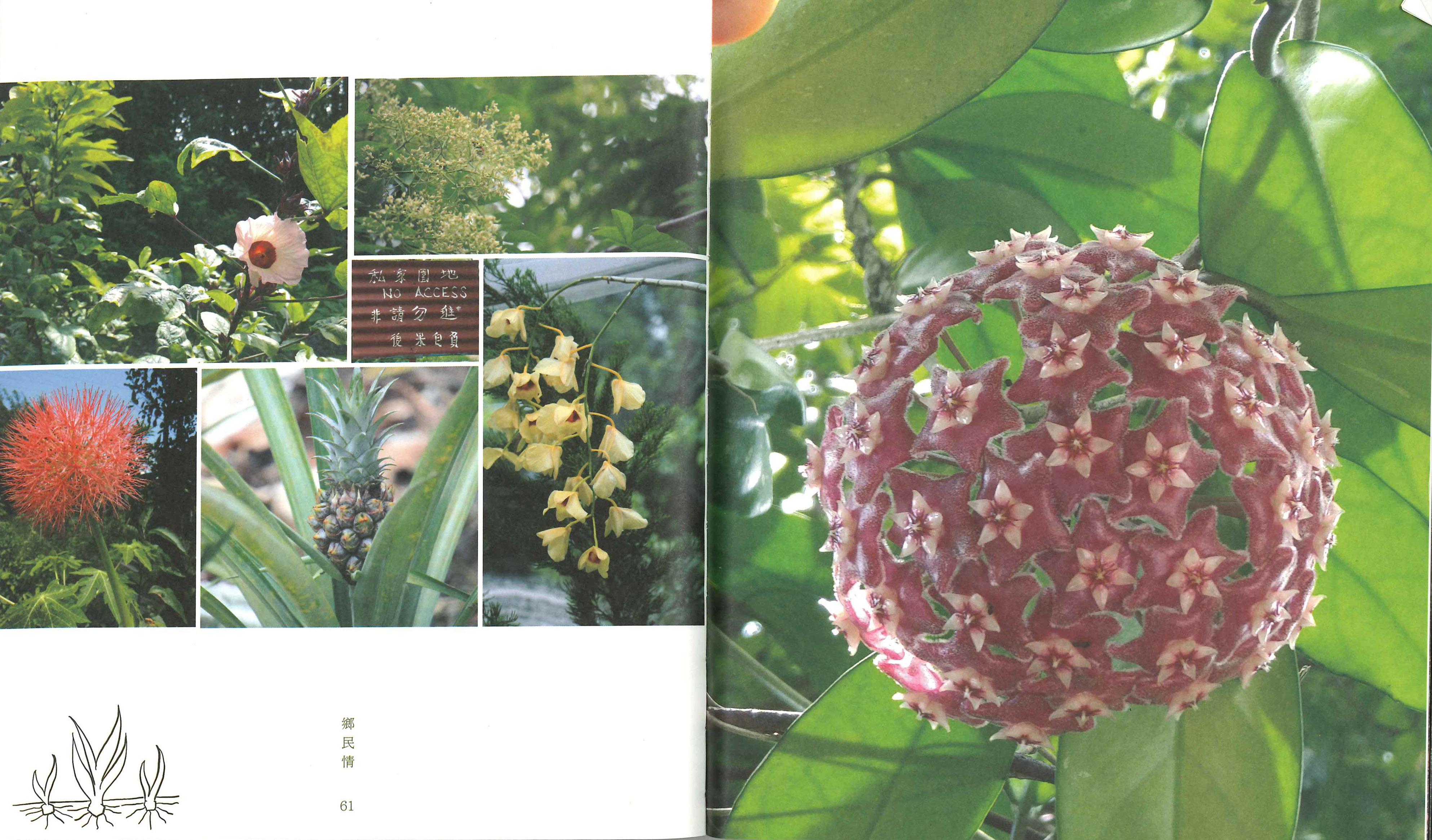

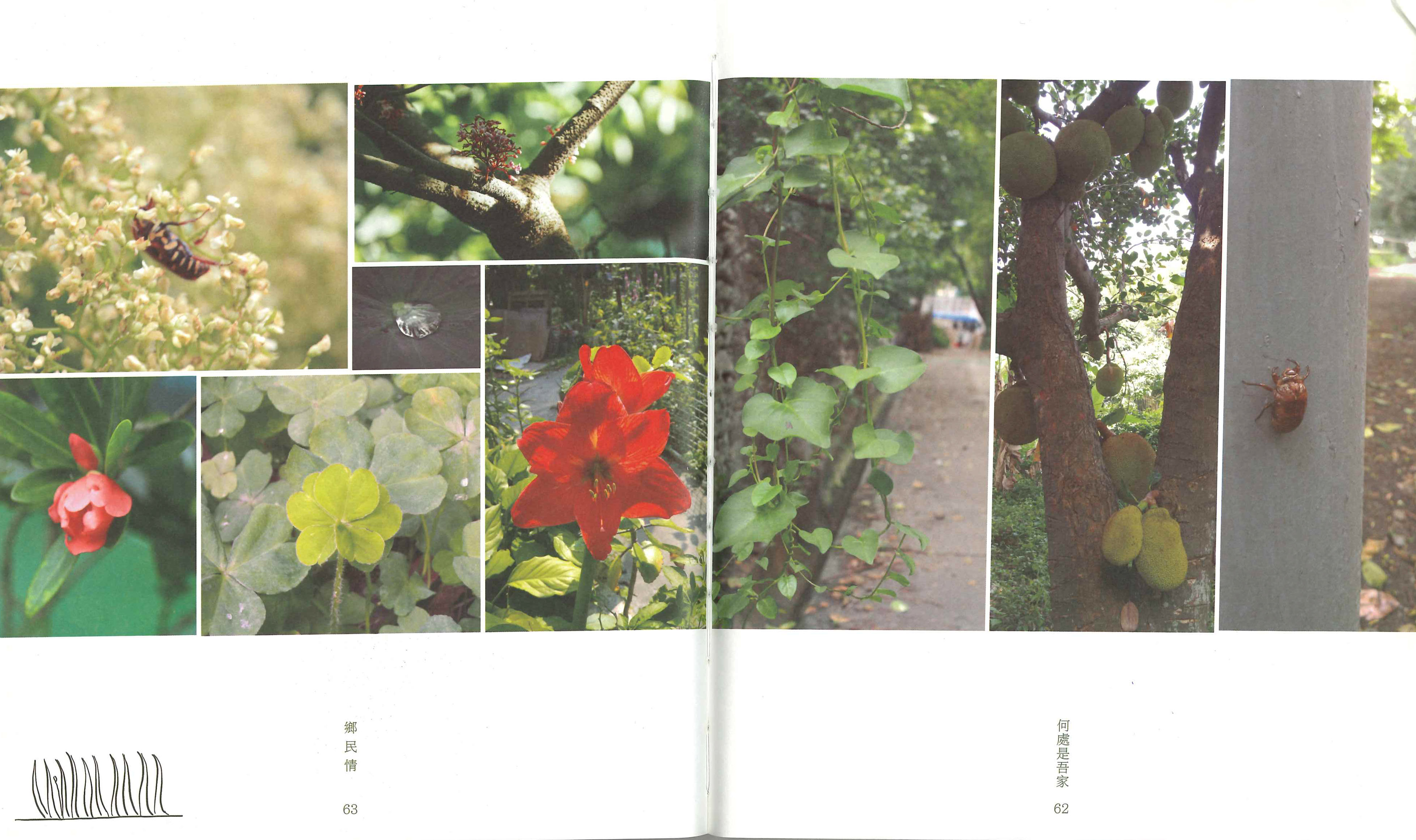

Among them, Edward Yiu Chung-yim proposed a win-win-win alternative, and the author Fung Ka Chun recorded the historical context of Wang Chau from the documents of the Hong Kong Public Records Office, "The location of the Wang Chau Development Project today is just one street away from the urban area of Yuen Long. In fact, when Yuen Long began to develop new towns in the 1970s and 1980s, Wang Chau was not selected for large-scale construction projects. Even the urbanization scale expanded later. It mainly developed east and west along the Castle Peak Road. Even the construction of industrial estates did not affect the current development area of Wang Chau." And various photographers also recorded the plants found in Wang Chau in the book.

|

|

Cover page of “Where is My Home - Wang Chau.” Published by BLEU Publications Ltd. |

|

|

Inside pages of “Where is My Home - Wang Chau,” photographers took many photos of plants in Wang Chau. BLEU Publications Ltd publishes the book. |

|

|

Inside pages of “Where is My Home - Wang Chau,” photographers took many photos of plants in Wang Chau. BLEU Publications Ltd publishes the book. |

Whenever art and social movements overlap, we often ask: when is the resistance, and when is the artistic creation? This case study may not provide a perfect answer, but in Wang Chau, the villagers kept emphasizing the plant life in the green belt of the villages. From imagining the jackfruit as a woman and deliberately documenting the plants in the villages with photos, plants are actually inseparable from them. In fact, four female villagers are preparing pictures of Chinese herbal medicines they planted to share traditional wisdom in the villages. And this kind of daily farming practice is a real-life in Wang Chau that any art form of resistance cannot replace.

|

|

Farmland of Ms Cheng, a villager in Wang Chau. Photo by the research team. |

|

|

Farmland of Ms Cheng, a villager in Wang Chau. Photo by the research team. |